Is a relationship costing you a lot of energy? Do you feel the drama building up again? Chances are there is a destructive pattern we call the drama triangle.

Spoiler-alert: you have a stake in it yourself!

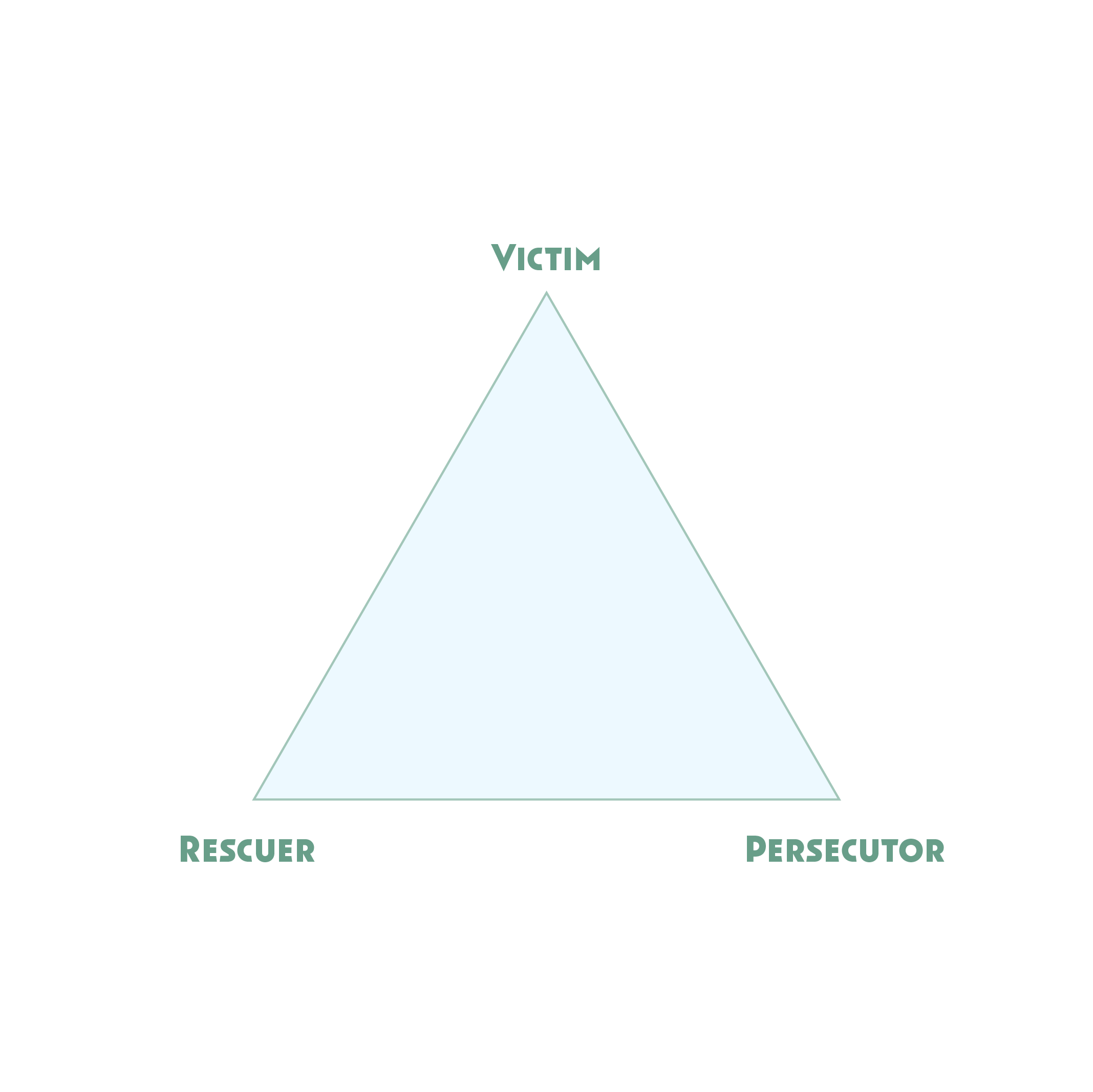

Soaps and intrigues are full of them. Dramas. In a good drama, there are three roles to play: the rescuer, the victim, and the persecutor.

The drama triangle can occur in both private and business relationships. It is also common in family and partner relationships.

According to Karpman, who developed the drama triangle from Transactional Analysis, the intention of every role is good. But somewhere something goes wrong and only 10 per cent of the good intentions remain.

- This is how the Victim disregards their own resolution options. . .

- The Rescuer keeps the victim dependent and does not trust that the person can do it themselves.

- The Persecutor thinks he is feeling good by rejecting others.

Courage

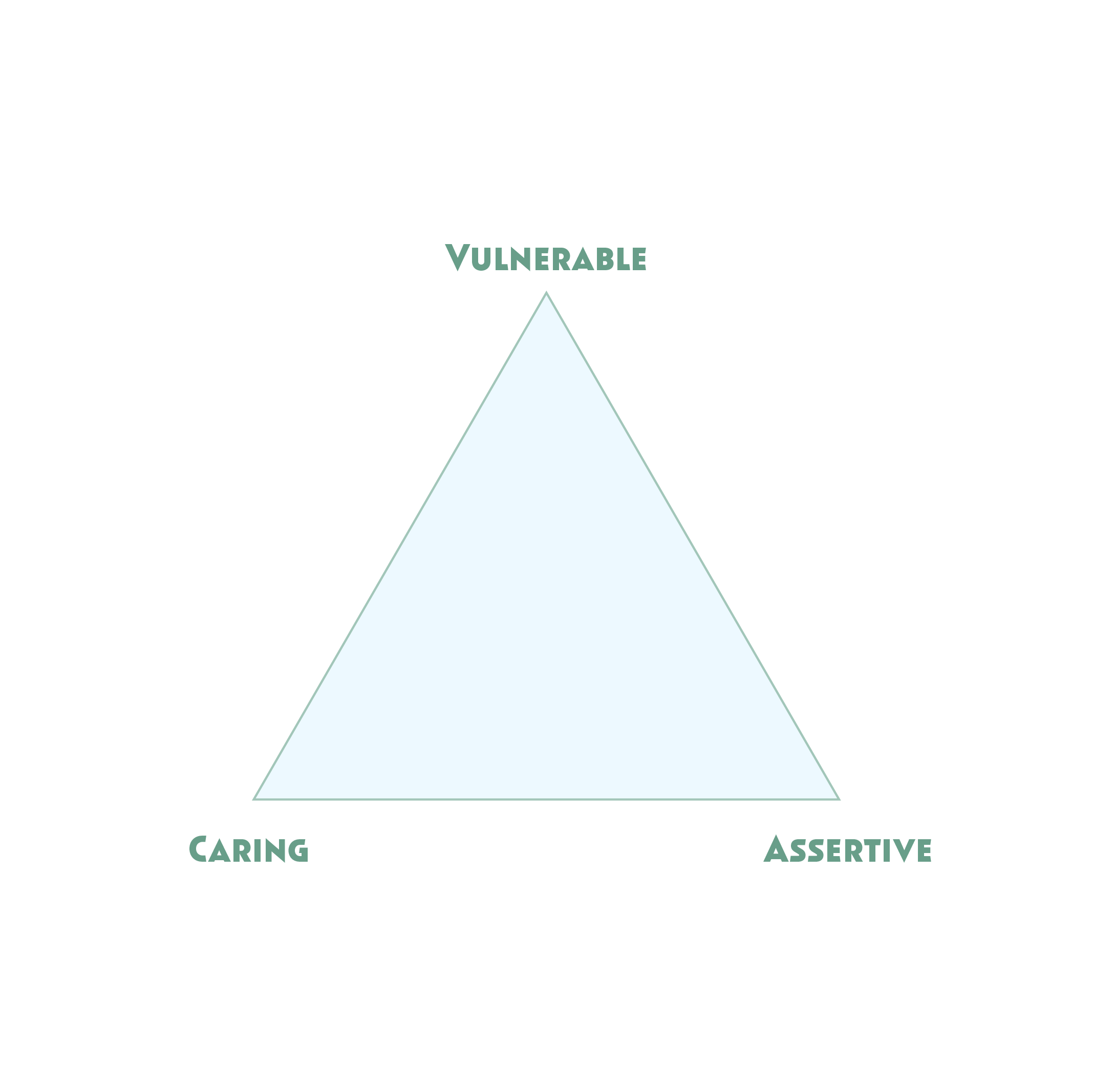

It takes guts to avoid this psychological game and deal with the reality.. Being open about what you need, setting boundaries and taking personal responsibility.

- it requires the Victim to act realistically , to take responsibility for their own thoughts, feelings and needs. Making oneself vulnerable and actively seeking solutions to problems. towards solutions for problems.

- The Rescuer shifts to positively helping and doing nothing more or less than agreed.

- The Persecutor can give positive feedback without hurting the other person and be clear about their own boundaries.

Does this sound familiar? How to get from the drama triangle to a winner's triangle.

Let me provide two examples from my practice:

1 In my work as a psychologist, I meet two parents who have a son who uses drugs. They want to do everything they can to put him on the right path. They have noticed that he has been stealing money and smoking in the house despite prohibition. He keeps promising to get better. It costs the mother in particular a lot with energy and she is at her wit's end. They have had many conversations with the son, in which the parents came to agreements for change. But time after time, things went wrong and they discovered that he was using again anyway.

2 During an executive leadership retreat, a participant brings up a conflict he has with his fellow executive. The latter constantly interferes with his work. Much of the group contributes suggestions and advice. Despite these being good, each time the participant says he has already tried something like this. With each advice, he emphasises why it does not work. The feeling that arises among the group is helplessness. The conversation seems to go in circles and meanwhile nothing changes.

Especially if you have this feeling more often with someone, ask yourself what is really happening. The drama triangle, as mentioned, has three roles. I describe them briefly.

The victim role

The word ‘victim’ may sound a bit heavy-handed. With this attitude, someone implicitly or explicitly gives the message that they are suffering from a situation. The victim often evokes a feeling in you that you should help him or her.

For example, when:

- A friend who comes to you for advice;

- A colleague struggling with a conflict with another colleague and asking you for advice;

- a partner who is resentful for a long time because you did not do what he or she had hoped.

"I am not okay"

"I am okay"

The rescuer role

From this role, you do all sorts of things to please the other person (the victim). You can do this by:

- being nice;

- being helpful;

- giving advice and/or

- provide solutions that you are convinced will help.

If you do this from the rescuer role, you will discover to your surprise that your colleague, friend or partner is not cheering and happy with the solutions, but resisting. The reaction you get is from the accuser role in the other person.

From the example above, both parents as well as the other participants during the retreat did their best to help and encourage the other to change. This did not lead to an enthusiastic response.

The persecutor role

Now comes the frustration. Nothing changes, not even a thank you, all that energy put in for nothing. Thank you for nothing.

Because as in the example, the son continued to use drugs. Despite all efforts and agreements. Even the retreat participant turned out not to have done anything with the advice. The rescuer then still feels responsible for the other person and continues to help. How does that work?

Persecutor and victim are in fact one and the same person. There is just a different role. Perhaps unintentionally, advice, solutions, and the like are dismissed by the accuser with comments like:

- ‘You don't really understand what I'm going through...’;

- ‘It's easy for you to talk, but in MY situation....’;

- ‘I already tried something like that, and it didn't work’.

The mood of the statements is: ‘ yes-but...’. When the first yes-but falls, he is basically saying ‘no’ to what you say. The persecutor does not always have to say something. Even by doing nothing, the rescuer experiences the message that he has not done well (enough).

The rescuer responds to the persecutor role by saving even more. First he does so out of love or commitment, then irritation, helplessness, and eventually fatigue set in. This fatigue can lead to burnout symptoms.

In fact, both victim and rescuer are trapped in the same system. The rescuer actually believes that what he does has a positive effect on the victim. The victim feeds that belief through his behaviour.

"You are not okay"

You're perpetuating it yourself.

Despite all the rescuer's good intentions, nothing changes in the victim. As a helper, you may ask yourself, ‘Am I actually helping the other person?’ and ‘Is anything really changing?’. And if the honest answer is ‘not’, or ‘not yet’, chances are you have been caught up in the drama triangle.

Because it is not in the quality of your advice, the solutions provided, your service attitude, the best intention. It is in the victim's attitude. There is something in the victim's attitude that causes all your attempts to help to fail.

The problem the victim is struggling with is not that he or she lacks knowledge, or that your help is no good, but that he is afraid.

This fear can be the fear of:

- change;

- responsibilities;

- growing up;

- the consequence of choices

1 The son has problems becoming an adult and coping with responsibility. Because he finds it difficult to handle his fears, it is easier to remain addicted. Addiction is for him a solution, an escape route.

2 In the retreat example, the participant is actually afraid of the conflict. He believes the conflict could derail so much that he could lose his job. And he cannot handle that.

The blind spot

What you don't or can't see as a rescuer is that helping actually perpetuates the behaviour. The rescuer is protecting the victim from (more) pain. You are not teaching him to deal with frustration and pain.

In the role of rescuer, you try incredibly hard, while the victim just sits back and criticises, so to speak. In fact, the victim is not a problem owner. As long as the rescuer keeps rescuing, the victim does not have to move. From a compassion or love perspective, this is understandable, but you can admit to yourself that of the two, you work the hardest.

You often hear the rescuer making statements like:

- ‘As long as I can still influence him, there is hope for change’

- ‘If I don't help, things will get completely out of hand’

- ‘If I stop helping, he will collapse’

- ‘If I stop helping, he will be completely unhappy’

1 These are exactly the concerns the parents had. They begin to see that their son actually has a luxury hotel at their house. In fact, all he has to do is regularly say ‘sorry’ and promise improvement and tempers are once again calmed. He does not have to change because there are no serious consequences. The parents become aware that they have believed in an illusion, namely his change. They understand that they will never be able to shoulder the responsibility of their son's life.

Despite their efforts, they cannot force their son to be happy. By discussing estimation of the actual dangers of quitting saving, they can look at his addiction more realistically. The son has to learn to stand on his own two feet.

2 During the retreat, we get into a conversation as a group about how continuing to advise and help will not move our participant forward. Engaging in conflict is exciting. Group members begin to see that their feelings of powerlessness are a logical consequence of the drama triangle. This puts the focus of the conversation on feelings that are on everyone's mind. When participants say ‘I can't’, they are actually saying ‘I don't want to’.

We can do our best to help the other person, but the other person ultimately chooses for or against the change, for or against life. However, we can do our best to guide and support the other person towards problem ownership.

By maintaining the status quo, a victim does not have to face his pain and fears and take matters into his own hands.

We are better off teaching someone to deal with pain than continuing to protect them from it. I once wrote a blog about how the painful experiences in our lives are our greatest teachers.

The persecutor protests

Now you must be thinking ‘I'll stop saving’. Exactly. And then prepare to face resistance. The persecutor will pull out all the stops to avoid changing. The predictable reactions are:

- 'You can't do this to me';

- ‘I'm going to collapse’;

- ‘I thought I could trust you’;

- ‘You are the only one who makes me happy’;

- ‘I thought you were my friend’

These statements often provoke discussions that can lead the rescuer to doubt himself. As long as that happens, the conversation need not be about the real problem: the fear of responsibility, growing up, etc. Not that I believe anyone deliberately chooses the victim role. Usually, there is no intentionality. Rather, victimisation often comes from not being aware of one's own strengths and abilities.

Emotional honesty is the solution

Emotional honesty means that both learn to talk about their deepest feelings and needs. By feelings, I think of disappointment, anger, fear, pain, sadness, and shame. The most difficult statement in a relationship is to say, ‘I need you’. Only when this statement is made from equality is a real encounter possible.

Such a conversation can only take place in connection, i.e. you actually give each other space to tell what is on your heart, while the other is fully available with their attention. After one has told everything, the roles are reversed, and the other can speak his heart out.

- Do not manipulate others by denouncing or bailing them out

- don't let yourself be manipulated

- look for options

- find out what you really want and then ask for it

- give and request sincere feedback and appreciation

- do not put energy into things you perceive as negative

- Appreciate yourself for avoiding the game

And if you are still in the Drama Triangle, getting out is always possible!

How it ended

You may be wondering how did that son turn out? Very well! The parents told their son that they wanted him out of the house and that they would help him find the right help for his drug problem. As to be expected, he pulled out all the stops to keep the situation unchanged. He accused them of being bad parents, that he would end up on the streets and then it would be their fault; he also said, ‘Are you Christians now?’

They stood firm because they knew this would help him best. With their help, he eventually joined a counselling agency. It became a difficult road to independence for him, but he succeeded. Through it all, the contact between the parents and their son has become closer.

And the student from the retreat? He learned to take the risk to make the conflict negotiable. He discovered that the disaster scenarios were mostly ghosts in his head and that he needed to become more ‘visible’ in what he did and did not like. In the days that followed, you saw him grow by showing more and more courage to stand up for himself.

Will you let me know if this helped you?